Any Happier I Would Just Pop Playboy Is Naked Again Cartoon

Features

Viewing Life Through a Twinkle

Eldon Dedini was known for the terminal 4 decades of his life for his painterly cartoons that regularly depicted frolicsome forest scenes inhabited by lascivious satyrs and plump, wanton forest nymphs, naked flesh glowing in Rubenesque hues in the pages of Playboy.

Merely Dedini's quirky cartoon comedy appeared start in Esquire, so in Saturday Evening Post, Collier'due south, and others in the general involvement market, so in The New Yorker (in boldly lined black-and-white with a wash) before it debuted in Playboy (in steamy luminous watercolor).

Merely Dedini's quirky cartoon comedy appeared start in Esquire, so in Saturday Evening Post, Collier'due south, and others in the general involvement market, so in The New Yorker (in boldly lined black-and-white with a wash) before it debuted in Playboy (in steamy luminous watercolor).

Gus Arriola, another supreme stylist whose Gordo comic strip was a stunning fiesta of design and color, counted Dedini his closest friend in a friendship of over fifty years that was grounded firmly in their mutual passion and respect for the visual art they practiced and in a unique esprit they shared, living in Carmel, California.

"Fifty-fifty his signature was a design," Arriola once said. "—assuming, succinct, an autograph as distinctive as the rich humor it identified. Simply, Dedini —much every bit one would say Bernini, Modigliani, Dali—Dedini—all those ending in -I appellations signifying loftier art. Few humorists can draw passably, if at all. Eldon was both an achieved illustrator and a proven humorist. His pictorial and literary recording of international events and domestic culture through his honor-winning years was always timely, e'er cogent and always remarkably funny."

Quoted in the Monterey Herald'south front-page obituary for Dedini in January 2006, Lee Lorenz, cartoon editor at The New Yorker for many of the years Dedini's cartoons were published therein, said: "While a meg people tin describe, very few tin can cartoon well. To be a cartoonist you have to be a stylist, and that'southward non easy to come by. Information technology transcends technique. And he was an excellent idea man. He had a wide-ranging imagination. He was tough to edit because he didn't need much editing. I never asked him to redraw, which at The New Yorker is quite unusual. If twentyth century cartooning is e'er looked at seriously," he concluded, "Eldon Dedini will exist one of the outstanding figures of American comic art."

"He could do anything with paint," said Playboy's cartoon editor Michelle Urry, who knew the cartoonist for over 30 years. "He knew anatomy brilliantly and he could throw away all those lines. And he was funny, very funny. I remember information technology was wonderful he came down to earth for us."

Recognized four times by the National Cartoonists Guild every bit the year'due south best magazine cartoonist (1958, 1961, 1964 and 1989), Dedini was a master of his medium. He was influenced by the radiant color of East. Sims Campbell, who specialized in those harem cartoons at Esquire. The severe simplification and commanding bold line of a Dedini drawing came, he said, from studying Peter Arno's cartoons and Whitney Darrow, Jr.'s in the venerable pages of The New Yorker.

Only in the last assay, his artistry was uniquely his own. He abstracted homo anatomy, redesigning and simplifying it to suit the pose and the motion-picture show. And so he cast the cartoon, creating the characters for their roles. All his men have bulbous noses and popular-eyes, merely each is an private caricatural design: the noses are not notwithstanding size and shape—they bend and hook, and bend and bulge differently, from face to confront. And the women, if they're one-time, are usually lumpy and frumpy, with noses to lucifer the men's. The young women, nevertheless, are erotic exaggerations, bosoms and buttocks galore, legs that become on forever, and perfectly oval porcelain faces, by and large heavily lashed eyes and smiles all tooth.

Dedini loved cartoon crowd scenes and elaborate costumes and architectural particular: after simplifying the elements of a limerick, he busy it with visual complexities—patterns of lines and shapes and colors, varied textures, habiliment that draped and swirled, building interiors with lofty vaulting ceilings and arched aisles and exteriors with antique sculpted knots and furbelows. Here'south a medieval castle, looming in its crenelation, being stormed by an unruly ground forces, described by the king on the parapet as "two hundred grand peasants from permissive homes."

Dedini'south sense of sense of humour was as antic equally his pictures: typically, it quirked, yoking a commonplace utterance to a fantastically unlikely speaker in a place neither belonged, creating a new and always hilarious scrap of being, and shedding thereby a liberating laughter and light on the human predicament. A vintage total-rigged sixteenth century sailing vessel, mayhap a Flemish man-of-war or Danish pinnace, its royal stern toward u.s.a., with a fair wind and a post-obit sea, flight the Jolly Roger, its helm on the quarterdeck, saying expansively, "I love the Caribbean in February."

Thus, our incongruities make us human being and unite united states all in a common weal. Just the cartoonist Dedini was more than a cartoonist; or, rather, the more than that he was made him a peachy cartoonist.

Subsequently Dedini'due south death, Arriola wrote to me: "I still tin't believe our beloved friend Eldon Dedini is gone. And as someone says, I don't have to believe information technology if I don't desire to. When I was introduced to Eldon in 1953, I sensed I was meeting someone of heartening substance. The following v-plus decades of neighborly activities in Carmel and Monterey more than proved that sense. Calling Eldon a cartoonist just christens the tip of an impressive iceberg. Beneath the surface is a superb painter, a remarkably inventive illustrator, philosopher, and humorist—a keen observer, revealing life'south little truths with his unerring brush. His chief reward was the viewer's invariable burst of laughter. He was a walking repository of eclectic knowledge about art, history, jazz, vino—you name information technology. I gave upward using my encyclopedia on a subject search: it was faster to pick up the phone and call Eldon.

"Too many of today's comics stand up and and then sit downwards, seemingly motivated by anger. Acrimony is not funny. Eldon was motivated by love, beloved of the visual arts, music, sports, literature, and nature—all revealed in his painterly treatment of homo'due south ridiculous foibles. Those of u.s. lucky to receive his personally designed birthday cards, year after yr, noted they were ever signed con amore. He was a man as giving of his time and his talent, aiding friends and organizations in need, as he was to his craft. He graced every social gathering with his delightful, informative sought-later on company. Amongst his peers, he was hailed as Male monarch not because he hailed from King Urban center but for his unique multi-talented persona and courtly demeanor. Famed names of Salinas Valley should in future read Steinbeck, Ricketts, Jeffers, and Dedini"—referring to the vicinity's celebrated novelist, biologist, poet, and, at present, cartoonist.

Although he sold cartoons to the nation'south nigh sophisticated magazines, all headquartered in Chicago or New York, Dedini lived all his life in California, most of information technology within a few miles of Male monarch City, where he was born Eldon Lawrence Dedini on July 29, 1921. "The Dedini family," he once wrote, "were originally butter and cheese makers. Immigrants in 1873 from Lavertezzo, Canton Ticino, Switzerland, on the Italian border. They fabricated butter and cheese in Corral de Tierra for thirty years, leasing from David Jacks, the land businesswoman. And so the family moved to King City in s Monterey County where I was born and escaped the butter and cheese business. It was with the blessings of my male parent and female parent, who said, 'Go! The ranch will always exist here if it doesn't work out.' I had been copying the funny papers since I was v years old, and by the age of thirteen, I'd discovered cartooning was a profession and decided to be a cartoonist."

Dedini grew upwardly in the Salinas Valley, "playing accordion at Italian-Swiss weddings and Mexican fiestas," he said. Very early, his art education began: "I copied the comic strip characters—Barney Google, Popeye—all of those, but I always liked magazine cartoons. And when Esquire came out, those colored drawings actually impressed me. I didn't exactly copy them—I made my ain. Barbara Shermund, Syd Hoff, Abner Dean—you can re-create them, but yous become them, you lot sink into them. And everybody said, Be original. So I did my own."

After high school, Dedini enrolled at Salinas Inferior College—now Hartnell Higher—whiling abroad the long daily bus ride with a deck of cards that he brought along to play Pedro in the back of the double-decker with friends. He took art courses at SJC but majored in general studies and then he'd have something to fall back on if cartooning didn't work out. Cheers to his fine art teacher—Leon Amyx—Dedini never needed to fall dorsum. Amyx, an accomplished watercolorist, had aspired in his youth to be a cartoonist, and he suggested that Dedini plug the cartooning hole in the art curriculum past volunteering at the local newspaper.

Interviewed by Lisa Crawford Watson at the Monterey Herald, Dedini explained: "I went to the Salinas Morning time Mail service and the Salinas Alphabetize Journal—now the Salinas Californian—and made an date with publisher Paul Caswell and editor Nelson Valjean to offer my cartoon services free in exchange for the experience. And it worked. They'd tell me the news, and I'd illustrate the point in a cartoon. My kickoff was about the train depot in Salinas and how information technology was falling autonomously." He paused before concluding the account with just a nudge of a punchline: "You've gotta kickoff somewhere," he said with a characteristic grin.

At eighteen, even so a educatee at SJC, Dedini sold his start cartoon to Esquire magazine. When he graduated, he took advice again from Amyx and went to Los Angeles and enrolled at the Chouinard Institute of Art, where many of the animators at Disney were preparation. At Chouinard, he met the adult female he would marry, Virginia Conroy, a painter and etcher.

"We were both on scholarships," Dedini said. "I was a janitor, and Virginia was a librarian. We got married the yr nosotros graduated, 1944, July xv. I went to piece of work for Universal Studios. Iii months later, all the studios except Disney went on strike, and then I went over to Disney."

During his first week at Disney, Dedini worked on model sheets, and another Disney artist gave him some advice: "Don't describe Pluto. Draw what Pluto is doing." Said Dedini: "For a cartoonist, those are key words to live by. Good advice for all fourth dimension."

Dedini honed his comedic talents doing storyboards. "I worked with writers. What they wrote, I put in a storyboard—a giant comic strip, which was perfect. It was a wonderful education. You draw possibly a hundred drawings a day—staging, laying it out. All day long. And if they rewrite the story, you re-depict the storyboards. You learn never to throw the drawings abroad considering a week later, they say, 'You know—what we had last week was better.' So I always kept the drawings in a drawer that I could go back to. I had some other drawer in my desk that Disney didn't know well-nigh—total of drawings I was trying to sell to Esquire. I too sold to all the little magazines—Click, Film, Bully, Estimate—five or ten dollars a drawing, and I idea I was in heaven. Merely I liked the full pages, not the small-scale cartoons in Collier's and Saturday Evening Mail service. I did some of them, but my heart wasn't in it."

He also joined a southern California watercolor group and learned about painting in color. At Disney during the day, he worked on such epics equally "Mickey and the Beanstalk," "Ichabod and Mr. Toad," and "Fun and Fancy Free." Nights and weekends at home, he drew cartoons and sold them through the mail. "When the nights began running into days," as Watson put it, "he knew it was time to commit to magazine cartooning."

In 1946 , he was helped to a decision past Esquire'south publisher, Dave Smart, who phoned the cartoonist and offered to double his Disney salary if he would work exclusively for the magazine, generating ideas for the other cartoonists as well every bit being featured himself. Dedini took the job, knowing that the gags are the near important part of cartooning.

"The gag thought is the whole secret of cartooning," he told Lisa Watson. "Style alone will never sell a bum joke. So you tin describe. A meg people tin can depict. The question is, are you funny?"

Dedini was funny for Esquire for the next four years. He sent in 100 ideas every month, tailoring them for the proclivities of specific cartoonists—hillbillies for Paul Webb; working grade men in their undershirts at home for Syd Hoff; the frilly-witted young things, Barbara Shermund; the heavy-set fix, Dorothy McKay. Any ideas that weren't farmed out to the Esquire stable came back to Dedini to describe.

In 1950, he gave upward the Esquire gig, taking Smart'due south advice when the publisher told him that he was set up for The New Yorker. Dedini was back in Monterey County by so, and he was soon one of The New Yorker's contract cartoonists: he showed all of his cartoons first to The New Yorker; any that the magazine didn't buy, he could offer elsewhere, and in render, The New Yorker provided some employee benefits similar health insurance. He continued selling as well to Esquire. Then came Playboy.

Playboy'south commencement event was published at the end of 1953, famously undated so information technology would stay on the stands until it sold out. Publisher Hugh Hefner, a frustrated cartoonist himself, aspired to muster a troupe of distinctive talent to work exclusively at his new magazine, and he had his center on Dedini almost from the start.

Dedini remembered: "In 1954, Hefner started writing me to say he wanted me at Playboy. Simply Esquire had put me on the map, and I felt a sure loyalty. Hefner wrote 4 or five years in a row and kept upping the price. By that fourth dimension, Esquire had been sold, so that did it."

Only about then, Dedini heard from another cartoonist who had but sold a drawing to Playboy and had been advised by Hefner to apply color "in the Dedini style." Said Dedini: "I figured that if they were going to teach people to work in my style, I'd better go far on some of it."

Most issues of the magazine later featured at least i full page color Dedini cartoon, and Dedini was soon a contract cartoonist with Playboy too every bit with The New Yorker, the seeming conflict resolved by the simple fact that cartoons for the onetime wouldn't exist appropriate for the latter. (Or weren't, so.)

In his Dedini obit for the New York Times, Douglas Martin wrote: "Dedini'south Playboy cartoons helped institute the mag'south image in the 1960s, from have-offs on classic Japanese erotica to urban hipsters. His sexually advised satyrs in joyful pursuit of astoundingly proportioned, equally lusty nymphs became as much a Playboy trademark as lascivious advice columns"—and equally familiar to readers as the centerfold pivot-ups, he might have added.

"My starting time cartoon appeared at that place in 1959," Dedini told Watson in October 2005, "and I've been with them ever since. I guess, since I still feel funny, I'll merely proceed going." He paused. "Until I don't."

Dedini loved the sophisticated wit of Esquire, and he loved the opportunity to work in color that Hefner's mag afforded him, merely for him, Playboy's focus was a trifle narrow. All the cartoons seemed to be focused on boys chasing afterwards girls—and communicable them, to the randy delight of both, which was not exactly Dedini's cup of tea. He reveled in life, his son Giulio told me: "He appreciated food, wine, people, humor, history, travel, family, sex, beautiful women, and the outdoors."

He gleefully manufactured ribald one-act in his Playboy cartoons, just, according to a brother-in-law, Charles Carey, he was very conservative in his ain relationships. Moreover, to Dedini, the usual Playboy cartoons were boring in the tautology of their constantly blissful libidinousness.

During a formal presentation at the Festival of Cartoon Art at Ohio State University in 2001, Dedini showed slides of his cartoons for both The New Yorker and Playboy. One of the latter depicted an orgy, a writhing pile of naked bodies—what Dedini chosen "the standard drawing" for Playboy. "I endeavor not to practise these too often," he said.

He tried to vary the standard, he continued, to reduce the monotony of the routine tableau of boys chasing girls all the time. "I discovered I could go to mythology and employ satyrs and so forth, and information technology opened upwards more ideas. The captions could vox very contemporary ideas but if you put them back at that place in those mythological times, the result is an extra dimension of humor." He showed a slide of a leering centaur maxim to his amply-rounded playmate, "Remember, what's an unnatural act for you is a natural act for me."

"I dearest to draw," Dedini said. "I oft beginning with a scene and no idea. I only draw a mythological scene, so leave the drawing lying around, looking at information technology every in one case in a while, keeping information technology in listen, and perchance I come up across a line in a paper article that fits, and I have a cartoon."

Continuing his search for ways to escape the standard Playboy cartoon, he came beyond Japanese erotic prints. "Well, no," he corrected himself. "They're not erotic. The ones I make are erotic. I sometimes copy Japanese caligraphy into the drawing, but I always alter something a niggling in case it means something I don't desire to say," he said with a sly smiling.

He resorted to history frequently, mimicking in caricature a well-known painting—for instance, the famous scene of the signing of the Annunciation of Independence, wherein a Dedini patriot, his quill pen poised, says, "Frankly, some of those truths don't seem self-evident to me."

Bruegel is a favorite of his. On one occasion, he imitated a Bruegel painting, cramming people into a typical multitudinous throng except that most of these Dedini Bruegelians were engaged in revelry of a more licentious sort than the Dutchman usually contemplated. In Dedini's version, one lone man stood in the midst of the orgy, raising his glass and saying, "Say—this is a nice light beer."

Ii cavemen in fauna skins sentry an extremely statuesque immature woman strut by in naked splendor, and ane of the men says, "The things you see when yous haven't got a club." While looking at this drawing, Dedini commented that he tried to get some socially redeeming stuff into his Playboy cartoons. Maybe, he wondered, this was feminist?

About a cartoon that didn't become a express joy from his audience, he said:. "Maybe it's not and then funny. But it's got girls in it. If you describe the scene with girls in it, Hefner and Michelle most of the time go for information technology."

Dedini didn't meet Hefner until he'd worked for the magazine for over twenty years. "I got messages, all the time," he said, "but I never met him. And I said to Michelle one time, 'I'd similar to meet him.' And she said, 'You lot wouldn't like him.' And she's his cartoon editor!" he marveled. "Simply I have met him, and I liked him," he beamed, "—of class, our life styles are entirely different."

Dedini was a disciplined worker. He drew every twenty-four hour period, starting at about v a.m., and every three weeks, he sent 25 cartoon roughs to Playboy and 25 different ones to The New Yorker. He estimated that he'd published about 1,200 cartoons in Playboy and over 600 in The New Yorker.

In 1963, his contract with The New Yorker stipulated that he be paid $iv.30 "per square inch" for the first twenty-five square inches of a published cartoon (for a 5x5-inch cartoon, he'd be paid $107.50) and $2.85 for "each foursquare inch above twenty-five." The understanding went on to specify bonuses that would be added to the bones rate depending upon how many cartoons the mag accustomed: after x cartoons had been accepted, he'd become a bonus of 12% added retroactively to what he'd been paid for those ten cartoons; on each of the next x cartoons, x%; and so on in x-cartoon increments until, subsequently forty cartoons had been accepted, he'd go a fifty% bonus. In 1968, the basic rate went up to $4.75 for the initial twenty-v square inches; $three.15 for boosted square inches. And the elaborate bonus schedule disappeared. Past 2004, the Byzantine scheme evaporated: he was paid $1,300 per drawing, covers starting at $4,500. His Playboy charge per unit at the same time was $i,700 for a full-page drawing.

"I've had good years and bad years at The New Yorker," he said. "Once I went for a whole yr without selling 1 in that location. I thought I was just out of business with them. I couldn't make 'em laugh there. And then, all of a sudden—I sold i, two, a 6. What they take and what they don't take is still a mystery to me after 50 years."

In concocting New Yorker cartoons, he used much the same tactics as he used with Playboy cartoons but without the amorous emphasis and torrid colour. He made historical allusions and sometimes imitated famous paintings. Once he invoked Chagall. "He always has people flying around in his paintings," Dedini said.

What could they be doing up in that location? And why? So he drew a nightscape with a Chagallian human and a woman in horizontal flying position over the rooftops below, the human saying, "I don't love you any more, Lucille, and I'one thousand dropping you off at your mother's firm."

During the Cold War, he loved doing New Yorker cartoons with Marx and Lenin in them. "I loved to draw them," he said. "They were the clowns to me."

"I like the subtle ones," he said, showing a drawing depicting a embankment with people seated on the sand, sunning themselves, the waves breaking in the distance. In the foreground, a father is answering his son'due south question: "Generations of our people take sat past the sea, my son, and when you are older and take sat by the sea, y'all will empathise."

Said Dedini: "It might be funny, eh?"

And hither'south Toulouse Lautrec, continuing in all his three-pes-high majesty before a mirror in a lid shop where he'due south trying on a towering elevation hat. The clerk says, "The derby is amend: that makes you wait like Abraham Lincoln."

In addition to the cartoons past which he earns his living, Dedini contributed artwork to numerous local Monterey enterprises and did posters for various civic events, including the annual Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance, a historic antique machine prove.

On November four, 2005, a show of his piece of work opened in Salinas at the Sasoontsi Gallery. Entitled "Broccoli and Babes," it ran until January three, 2006. Dedini'southward work belongs in museums: it satisfies museum-goer expectations in ways that much comics artwork on display in museums does not. In the first place, single panel cartoons can be experienced in a gallery in exactly the way that paintings and etchings are: the viewer strolls down the gallery, casually looking at the pictures on the wall, occasionally stopping to read the captions simply as he or she might stop to read the data placards affixed to the wall side by side to a Rembrandt or Watteau.

And expectations about comics are also handily satisfied: Dedini's cartoons brand y'all express joy. Then the desires of both art lovers and comics lovers are gratified, you might say. Merely there's more than here, even greater benefits to be savored. You don't laugh unless y'all read the caption and grasp its relationship to the motion picture it accompanies. Your laughter thus signals your appreciation of the verbal and visual blending of the cartoonist's art. So a third objective, one closer to my ain aesthetic heart, is realized in an exhibition of single panel cartoons.

What's more, with Dedini's cartoons nosotros tin can take nonetheless another step in appreciation, this time, back to the art lover who enters a gallery to enjoy the pure unadulterated visual artistry on display. Dedini'south cartoons are not merely funny; they're not merely adroit blends of words and pictures to comedic ends. They are also works of visual art. Dedini'southward pictures can be enjoyed in much the same mode nosotros enjoy Lautrec or Monet—as feasts for the eye and heart. Even more: it'south clear that many of Dedini's cartoons were inspired by his enjoyment of a picture or objet d'art that he saw somewhere, something that he wanted to, not copy, slavishly, but emulate, joyfully, in the manner of homage. We see this in his cartoons rendered in the manner of Japanese prints and in the mocking evocation of famous paintings and artistic styles. Looking at the lush richness of Dedini'due south watercolors, we tin often find objects in them depicted so lovingly that we know they stand for the well from which Dedini drew the refreshment of the flick he fabricated.

Oh, the broccoli? The babes are from Playboy, of grade, but Dedini has done a lot of humorous advertizement paintings for Isle of mann Packing in Salinas since 1985, when the president of the company persuaded the cartoonist to create provocative pictures promoting the product of the world's largest shipper of fresh broccoli.

The Salinas exhibit included drawing originals spanning his entire career, even some of the cartoons he did for the Salinas newspapers. "It really does come up full circle," Dedini said, "from my outset in Salinas to my return to Salinas."

In returning to the scenes of his youth in 1950, Dedini joined a colony of cartoonists who made their homes on the Monterey Peninsula. Virgil Partch, the famed "VIP," lived nearby in Carmel Valley, as did Bob Barnes, both magazine cartoonists. Hank Ketcham of Dennis the Menace fame was established in Monterey, and editorial cartoonist Vaughn Shoemaker, on the cusp of retirement, lived in Carmel and mailed his cartoons to his paper, the Chicago Daily News. And Jimmy Hatlo produced his syndicated panel cartoon They'll Do Information technology Every Time from a place chosen Tally Ho in downtown Carmel. Gus Arriola soon joined the colony. Dedini met Arriola when they served with Ketcham and Hatlo equally judges of a beauty pageant during the Monterey County Fair shortly after Dedini moved to boondocks.

In their judicial roles, the cartoonists were driven in the parade down Alvarado Street in brand new, shiny convertibles with the tops down. Their names and pictures of the characters they drew were plastered on the sides of the cars. "Our wives were there," Dedini remembered when we talked, "sitting in the cars. Some cute girl was driving. None of us were used to any of that. At that place were actually people lining the street."

The contest took place in the State Theater. The girls went strutting by in their swim suits, and the judges (and their wives) looked at them, and and then ane of them was alleged the winner.

"We were all there, huddled in the first row of seats in the theater," Dedini said. "I even have a photograph of that, our wives and ourselves, looking very young, looking up at the stage. We're all smiling and laughing. The judges expect a little serious, but non too serious. Information technology was slap-up fun. I remember Jimmy Hatlo especially—a cracking bon vivant, keen drinker. Very happy." He paused. "None of united states can remember the name of the girl who won."

It may have been the beauty contestants that supplied the crucial bonding goad, although it is but as likely that Dedini and Arriola, both gifted stylists at their craft, shared a passion for art. And a love of fellowship that would flourish at Doc's Lab. They became fast friends for life.

The playful sense of humor on display in Dedini's New Yorker and Playboy cartoons serves as a convivial introduction to the man, simply knowing him requires that we also know about Medico's Lab. Doc's Lab achieved its first chroma of fame in the pages of John Steinbeck'south 1945 novel, Cannery Row, which was about life at the tattered edges of the sardine fishing industry in Monterey in the 1930s. Medico was a character in the book, but he was more than a friendly fiction.

The existent Doc was Edward F. Ricketts, who moved to Monterey in well-nigh 1923 and set up the Pacific Biological Laboratory at 800 Ocean View Avenue. He operated the Lab in that location until he was killed in his motorcar at a railroad crossing in May 1948. Ricketts made a living furnishing alive marine specimens to high schools, universities, and medical research facilities. His occupation permitted him to practice the things he loved virtually—rummage the beaches and inland waterways of California for exotic creatures and pursue his own researches on marine life and the evolutionary procedure, nearly which he wrote numerous scientific papers. His research led him inexorably to the determination that all living things were part of an organic whole, the parts of which cannot be understood in separation from 1 another. Ricketts was, in brusk, one of the starting time ecologists.

From the outside, the weathered clapboard building on Cannery Row looks more similar a garage with a room on top than anything someone might mistake for a laboratory. Physician'south lab equipment was located in the basement—the garage part; he lived in the four upper rooms. The identify stood vacant after Physician's decease until 1951, when Harlan Watkins took up residence there, renting it from Yock Yee, the owner of Fly Chong Market across the street who had caused the Lab from Steinbeck, who had acquired it from Richetts.

Watkins had come to Monterey in 1946 to teach English at the loftier school. He was a bachelor and so he had plenty of spare fourth dimension to soak upward information on a vast array of topics. And he was passionate nearly jazz—the Dorseys, Ellington, Basie, Goodman, Shaw, James. Soon later on Watkins moved in, he started inviting people over for drinks and chat and jazz late on Wednesday afternoons. Some of the people were friends and colleagues. Some were not.

Said Dedini: "The all-time thing that e'er happened to me happened the evening Harlan telephoned and said, 'Report to Doc's Lab—yous have friends here.' I went. Until that moment, I'd never met him."

The remark captures the essential Dedini like no other: he was open to life, unquestioning in his acceptance of it in its various manifestations.

Watkins created a Wednesday ensemble of local personages—doctors, lawyers, architects, teachers, a sculptor, even a estimate, and, with the addition Dedini, Arriola and Ketcham, cartoonists. On any given Midweek, a oversupply of men eddied through the second-floor rooms, filling the air with fume and talk and laughter while a record actor tried to make itself heard.

Arriola recalled his first visit there: "We were awash with the bonhomie explicit in those rooms. The repartee so glib, so sharp, it sounded scripted. There was Harlan, stentorianly holding forth behind the bar with his expert friend and fellow teacher, Ed Larsh, the 2 seemingly conducting a seminar on everything. Politics, sports, jazz, literature, pedagogy, martini jokes—you proper noun it. And all with a scholarly control that welded your attention to the point so well you could take passed a written exam afterward. Skirting pedantry, the operative phrase was ever—enlightening fun. It was a club that didn't like to exist called a club. It was a men'southward club for men who didn't like clubs. Information technology was merely a grouping of—what'll I call them?—but guys that enjoyed beingness together."

Watkins gave upwards the place in nigh 1955 when he got married. And the Wednesday group was thrown into a country of panic.

"There were about eight or nine of us," Dedini told me, "and nosotros said, Where are we going to go every Wednesday night if we lose this identify? And then Harlan told us that he was paying $40 a calendar month rent, and the Chinese landlord beyond the street had often told him that for $60 a month, he could buy the place. I'k a trivial hazy: Harlan may have started proceedings to buy it, just we took over his option. We incorporated under the name Pacific Biological Laboratory in 1956."

And the Wednesday evening gatherings continued unabated.

At first, the PBL numbered less than a dozen, but information technology eventually reached nineteen or twenty. A typical evening at the Lab commenced after work on Wednesdays. Members, still mustered past Watkins, would begin collecting at five o'clock or five-thirty in the back room at the bar. Afterwards a drink or 2 and some conversation about their days' adventures, they'd brainstorm to play jazz records. Watkins might well launch into a lengthy disquisition uncovering some obscure scrap of vintage jazz lore, but his lectures were not confined solely to jazz. He was widely read, and what he hadn't read about, he could fake. He could fake such things considering he was forever curious about whatever hove into view.

As the afternoon faded into evening, the Wednesday denizens of Doctor's Lab listened less to the records and talked more. Sitting around that tiny room, they talked near politics and civil rights and books and their diverse professional triumphs and complaints. The variety of occupations and interests in the room widened perspective. "I learned nearly medicine and the law," Dedini said, "and they learned about cartooning. And we all learned nearly literature from Harlan."

Gradually, the music was background music. "Every at present then," Arriola remembered, "Harlan would get upward and postage stamp his foot and say, Mind to that—mind to that!"

About eight or eight-thirty, the group would rise and go together to dinner at a restaurant downward the street. "There were one or ii restaurants," Dedini said. "More like joints. Neil de Vaughn's wasn't bad." The group ate at de Vaughn'southward and connected their conversations. For several hours, Dedini remembered.

Members often brought guests to the Lab. After a three-twenty-four hour period workshop on "creativity" at the Academy of California at Berkeley, Arriola showed up with Max Shulman and Dedini with Art Buchwald. Not all the guests were famous. Ane fourth dimension, Watkins invited a Cannery Row habitue named Grant Mclean, nicknamed Gabe. Gabe was Steinbeck's model for Mack in the novel. At de Vaughn's, Watkins seated Gabe adjacent to Dedini, who was a sort of factotum (secretary-treasurer) of PBL and therefore sat at the head of the tabular array. Later, Dedini reported that during dinner, Gabe (or Mack) moisture his pants and some of the byproduct constitute its fashion into Dedini'due south shoe. Being an officer has its drawbacks.

After the ritual dinner at de Vaughn'due south, the group ever returned to the Lab for an subsequently-dinner drink. And more jazz. "Nosotros'd play jazz," Dedini said, "I would say until midnight, i o'clock—sometimes two or iii in the morning. Non everybody. The doctors would say, I've got an operation in the morning; I'd better get. Sometimes cartoonists, who don't know what they're doing, stayed later. But nosotros had deadlines, too. Many a time, ane of the doctors would get a telephone call and say, I gotta go deliver a baby. He'd say, I may be dorsum; I may not. And if everything went well, he'd come back. The music, the jazz, was the key thing. We would bring our own records that we liked from dwelling, and play them for the others. And we'd discuss the music. We became authorities. At least on absurd jazz, Due west Coast jazz, bop—music was changing in those days. The Monterey Jazz Festival started in the 1950s," he connected. "And a proficient many of the Lab members were on the Board of the Monterey Jazz Festival when it started."

The Monterey Jazz Festival was born in the imaginations of disc jockey Jimmy Lyons and newspaperman Ralph Gleason of the San Francisco Relate, who, at the time, was conducting the only newspaper column devoted exclusively to jazz. They dreamed of an outdoor jazz festival. And they started talking virtually Monterey as the site for it after having visited and imbibed both drink and jazz lore at Doc's Lab. "The Jazz Festival was born correct hither at this bar," Arriola told me. The first Festival opened on October 3, 1958, and amidst the performers were Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, and Billie Vacation, but 9 months before she died.

During an intermission at one year's Festival, Dedini and some other PBL members went up on stage to have their photograph taken. Duke Ellington was even so on stage, seated at the pianoforte, putting eye drops in his eyes. When Dedini was introduced equally "a cartoonist who sometimes draws jazz cartoons," Ellington got up and, without saying a give-and-take, pulled out his wallet and started looking through it as he meandered, frantically, effectually the platform. Finally, he found what he was looking for, a folded up magazine clipping. He carefully unfolded it and spread it out on the piano: information technology was a cartoon Dedini had washed for Collier'south.

The cartoon depicted 2 Russians in Red Foursquare, one of whom is apparently a dealer in blackmarket phonograph records: he has opened his coat to evidence the other fellow the tape that he has tucked inside, saying, " ... Cootie Williams, trumpet; Johnny Hodges, alto sax; Barney Bigard, clarinet; Harry Carney, baritone sax; Duke Ellington, piano ..." Said Dedini: "Ellington loved that cartoon because when he toured Russia the people of Russia loved his music, but they couldn't buy the records."

For years thereafter, Ellington sent Dedini a Christmas carte du jour. "I take virtually twenty," Dedini said. "He sends them in June."

Dedini cartoons turned upwardly everywhere. On a trek to the wineries in Napa Valley, the PBL crew visited Martini's old winery, and they noticed one of Dedini's cartoons neatly tacked to a door. When they introduced the cartoonist, their escort alleged, "Don't go out" and went to get his boss, Louis Martini. After Dedini autographed the cartoon, the old man invited all five of the grouping into his home for a spaghetti lunch.

During the Kennedy years, Dedini drew a cartoon in which a couple of tourists in Egypt are contemplating the Sphinx, which looks remarkably like the First Lady. One of the tourists says, "I don't know. Lately, everything looks similar Jackie Kennedy to me." Soon after the cartoon was published, Dedini got a note on White Business firm stationery, requesting the original. He complied. Afterwards Jackie'due south decease, Dedini's cartoon was among her personal items that were sold at a celebrated auction.

When the Jazz Festival was in session, some of the musicians would come by Doc's Lab after their performances and jam into the wee hours.

"We'd have a few drinks and talk nearly starting our own Cannery Row Jazz label," Dedini said. "And Gus and I would sit in the political party room at the Lab, drawing up logo designs and record jackets."

The walls of the 2nd floor rooms were eventually plastered with colorful souvenirs of these efforts—these and others. Posters and other artifacts designed by Arriola or Dedini for community events often became a permanent part of the decor, remaining on the wall long after the events they were intended to advertise.

The organization of PBL was ferociously informal. In writing nearly Doc'due south Lab years later on, Ed Larsh took pride in the realization that no one in the group ever thought of it as a social club. Nevertheless the corporation that owned the place had a membership: these were the people who paid dues sufficient over thirty-5 years to buy the Lab. Men became members past unanimous acceptance; but there was never a vote. They decided to restrict their number to well-nigh twenty, just they accepted many "permanent guests" who were not members but were ever welcome.

The group held numerous parties at the Lab on days or nights other than Wednesdays. Many of these affairs were in laurels of their wives (or, perhaps, to pacify them for putting up with their husbands' coming abode in the wee hours every Th morn later a Wednesday bout at the Lab all nighttime). The group also had its own wine label, and various of its members made periodic trips to Hecker Pass, where they bought cases of gallons of wine or, fifty-fifty, barrels of it. Then in the basement of the Lab, they'd canteen the wine and braze their label, using second-hand bottles from de Vaughn's.

Doc's Lab was more than a place. It was a feeling, an ambiance. "We were just going there to heed to music and have a beer or two," Larsh wrote. "But we discovered that the place has a kind of magic nearly it."

For Larsh, the spell was cast by the shade of Ed Ricketts, charismatic abet for ecology and non-teleological thinking. For Ricketts, everything was continued: information technology was all part of a communal wholeness, a glorious web of being in which all living besides every bit inanimate things had a place and function and depended upon one another in a grand harmonious scheme. In Doc's Lab under the aegis of Harlan Watkins, the additional conjuring was done by the music and the drinks and the fellowship. Sitting together silently listening to jazz, the men were enveloped by an oceanic feeling; all other concerns evaporated in the sound, and a transcendent awareness of at-i-ness in some sort of split universe bonded the group. A sense of customs and fellowship prevailed and remained with them even after the sound of the music faded.

Past the time I met Dedini and Arriola in 1997, the PBL no longer convened regularly. Concerned about the historic associations of the place, the members were eager to assure its preservation, and to that purpose, they sold information technology to the city of Monterey several years ago. "It's even so our gild," Arriola told me. "The city owns information technology, but we take the utilise of it until the last one of us goes. We're all aging. We kid about it being a last man club."

I visited Dedini in his hillside home and studio in the summer of 2004, during one of my almanac pilgrimages to Carmel. One wall of his livingroom is windows that open onto a deck. From the deck, nosotros could run across, through some encroaching copse, Carmel Valley in the altitude. Around the living room and the bordering studio were stacks of magazines—"For research," Dedini explained. And bookshelves in his studio were laden with books.

One wall was a bulletin board on which were tacked photographs of friends (one of Dedini with Ketcham and Arriola) and famous personages (Louis Armstrong, Jean Belmondo, Phil Silvers), postcards, sketches, and numerous of his ain cartoons, sometimes clippings, sometimes originals, matted for display simply often overlapping each other and other fragments pinned to the wall. Scattered among the pictorial matter were various bits of paper, each neatly lettered with slogans or sayings: "Ideas cannot be endemic; they belong to whoever understands them. Dying is easy; one-act is hard. Never go to a young doctor or an old barber. The more opinions you take, the less y'all meet."

On a shelf beneath this array were some record albums, a half-dozen unopened bottles of wine, and a radio. Leaning up against the chiffonier nether the shelf were several of his colour cartoon originals, matted and framed—and, in several instances, unfinished.

Dedini explained that he almost never finishes a cartoon at a unmarried sitting. After experimenting with various compositions, he selects the one that pleases him and sketches it with charcoal outlines onto watercolor paper. Then he begins to paint. He paints until he gets to a place where he hasn't decided what color, say, or texture to deploy. Then he stops. He puts the unfinished fine art in a matted frame and lets it marinate for a while, sometimes for days, while he does other things. Sometimes, he said, he takes the framed unfinished cartoon into the bedroom at night and stares at information technology as he falls asleep. "I go along looking at it out of the corner of my heart," he said. "I let it tell me, slowly, what it needs." And when it gets through telling him, he finishes it.

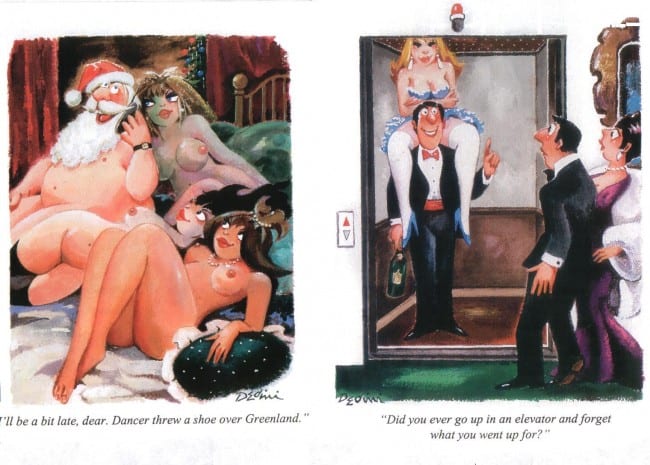

Two of the unfinished cartoons I saw were intended for the Christmas holiday issues of Playboy. Ane showed a plump, naked Santa gamboling in bed with three naked women in glorious embonpoint. Santa is talking into his jail cell phone: "I'll be a bit late, dear. Dancer threw a shoe over Greenland." The women are all grinning. Santa was completely colored, merely none of the women were. As he contemplated the picture, Dedini said, it seemed to him that if he applied mankind tones to all the women, there would be merely entirely besides much flesh color in the final rendering; so he stopped, hoping he would figure out a mode to finish the coloring and avoid the monotonous hue. In the published drawing, he made one woman's skin lighter than another's, and the 3rd, positioned somewhat behind Santa, is tinged with light-green and gray as if in the half-calorie-free of the bedroom.

The other unfinished art depicted a couple standing balked in front of an elevator, which has merely opened to reveal a man standing within, property a bottle in one hand, with a zaftig woman sitting on his shoulders, her legs wrapped effectually his neck from behind. He says to the astonished couple, "Did you ever go up in an elevator and forget what yous went upwardly for?"

Consummate nonsense, of grade. The joke, Dedini said, originated in that familiar circumstance: "Did you always go up to practise something and forget what information technology was before you got to it? Well, this guy ..." and he nodded in the direction of the cartoon, his explanation dissolving into laughter.

When published, all the characters in the elevator cartoon had been colored; everything else was stark white nonetheless. The interior of the lift and the walls were colored muted grays and browns, nothing, in other words, extravagant that would detract from the pictures of the people.

As nosotros talked, I finally couldn't resist asking the question that pesters every cartoonist: "Where do you get your ideas?" I said.

"I'll show you," he said, and he got up and went beyond the room and picked upwards a black, 9x12-inch square-spine sketchbook. He brought it dorsum, sat down side by side to me, and opened the book to show me. On the pages of the volume were pasted pictures clipped from magazines—advertising fine art, photographs of landscapes or odd buildings, picturesque cottages, famous paintings, portraits of medieval kings and queens, actors and actresses, elaborate costumes, random designs. On the pages facing the pasted-in clippings were Dedini sketches and notes. The sketches ofttimes echoed, without imitating precisely, the clipped art on the facing page.

"See here," Dedini said, pointing to a clipped fragment of a picture of an Arabian potentate in elaborate turban and colorful cloak, "I thought there might be something in this ..." On the facing page was a drawing of a man's head enveloped in a monstrous turban dripping with jewels. Non yet a drawing, just a funny moving-picture show. Eventually, Dedini used the thought in a Playboy cartoon.

"I make these books," Dedini continued, "and when I'g looking for ideas, I thumb through these."

A couple years later Dedini died, I went through several of his sketch/scrapbooks, then in the collection at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio Land University. His sketches and pasted-in clippings were accompanied by notes, some of which elaborated on the pictures, but many of these jottings had nothing to do with them: they were simply Dedini'due south notes to himself. "For a Mozart poster," said one notation, "—effort inks, washes and acrylic. Hints of Kandinsky."

"In painting Playboy cartoons," said some other, "try brush strokes in some areas a-la cubist-Cezanne handling. Break up flat areas with different tones of colour to get interest, motion, excitement to otherwise dull space. Even to the figures, furniture and whatever."

"Try for a new await style. Endeavour pen drawings. Try a collage of pen sketches. How much cross-hatch?"

In add-on to notes most drawing techniques, there are pages recording candidates for cartoon captions; no pictures, just circumlocution: First time caller; long time listener. I feel I'm slipping into significance. Bi-polar? I was double-parked in a no parking zone. Bi-polar zone? God's American. Treated and released. Is in that location a Mrs. Saddam? Do you think I like being bald? He's mostly grunts. Ascertain success on her own terms. Legal steroids. I dreamed all night about frozen embryos. Air kisses. Inconspicuous consumption. Downwards with oatmeal! What churns my butter is ... A warlord's piece of work is never done. Right-wing drunks. I may be hapless, simply ... Free range pork, beef, etc. Victoria'south secret, Veronica's secret. Immature animalism—where the hell's information technology gone? I call back I was stolen as a child. Now, do you happen to accept a glass of whiskey handy?

Later, in his customary manner, Dedini might draw a picture he liked, and then, lacking a caption, he'd page through the sketch/scrapbook, finding, eventually, a caption that could be incongruously coupled to the movie.

The result might be a cartoon similar the ane Playboy'southward Michelle Urry wrote to Dedini nigh, commenting on a cartoon canonical by Hefner: "'Fresh figs are now being served in the bedroom.' I love this, and I tin can't believe he went for information technology. It is such an unlikely and ecstatically silly line but it'south and then like you, poetic and knowing all in the same breath."

From newspapers and magazines, clippings quoting scraps of wisdom or observations filled the sketch/scrapbook pages. "Every country gets the circus it deserves. Spain gets bull fights. Italian republic gets the Catholic church. America gets Hollywood"—Erica Jong

Quotations copied from unidentified sources: "Annibale Caracci was the commencement to employ the word extravaganza . He used it to describe the drawings he made poking fun at the physical peculiarities of people he sketched during his walks."

A clipping quoting an unknown source: "People who take the evidence of their senses tin can exist divided into three not-professional categories: saints, simpletons, and humorists. The mass of flesh is insulated from these several species of misfortune by virtue of the fact that they know ameliorate than to trust plain experience."

And this: "'I believe in the sun, even when it is not shining. I believe in love even when I feel it non. I believe in God even when he is silent.' Words found written on the wall of a cellar in Cologne, Deutschland, later Earth War II."

And this 1 sounds like Dedini: "Why practise they put pictures of criminals in the Postal service Office? What are nosotros supposed to do—write them? Why don't they just put their pictures on the postage stamps so the mailmen can look for them while they deliver the mail?"

Pasted in 1 sketch/scrapbook is an undated pencil draft of a letter to Irving Phillips, who was and so producing the syndicated newspaper panel cartoon The Strange World of Mister Mum. Phillips had patently approached Dedini about collaborating on a console drawing featuring pretty girls. I'm quoting the entire letter here because of the insight it offers into the workings of Dedini's mind and his gentlemanly diffidence in turning down Phillips' proposition:

"Honey Mr. Phillips—This has been a soul-searching time for me, thinking over your offer of drawing the girl console. It'south not an easy decision for I'thou still engrossed in the freelance concept of 'my life.' I'chiliad honestly non yet ready to let go of it and would undoubtedly practice newspaper work. Doing both at the same time would undoubtedly conflict and not exist off-white to either. Your panel I would hope to exist a tremendous success, and information technology would then be 'my life.'

"Nada wrong with that! Except right now I'm fulfilled to a point (non coin, unfortunately, but in desires and hopes!) within the mag field. It scares me to death sometimes but until a drastic modify occurs, I must continue for a while notwithstanding as I am.

"Recently I've idea seriously about doing (creating) a newspaper panel. It'due south still too vague in my mind what or how information technology would be just the urge gets more urgent sometimes.

"You don't know how close I came to saying, 'Yep—let'due south become!' I am listening. It's wonderful to hear that you're wanted. But—

"I know well your by work, The World of Mr. Mum. ... I regret that we won't interact on this, but please keep the faith. I'm a cartoonist for life, and everything changes."

When looking for ideas, Dedini likewise consulted (in improver to the sketch/scrapbooks) his "research department"—all those magazines stacked throughout the house. In one case he saw a spectacular 2-page magazine advertizement for women'due south clothes, gorgeous models marching across two-folio spread in a parade of way and femininity. "And I thought, I'd honey to depict that, the wearing apparel, the girls," he said, "—and then I did." Merely for the fun of it. And then, he drew a man in the line-upwardly, and that created a situation begging for a gag. He institute the gag in the personal columns of the Village Vox, which he repeated verbatim in the cartoon, a deadpan recitation of the advertiser'southward search for a liberated roommate.

Dedini's creative process often began with visual images. Looking at other fine art or photographs, he played with the images and the connections he could conjure up between those and some fragment of conversation—all those candidates for captions in his sketch/scrapbooks.

"Michelle says I should make my women prettier," he said, looking at the woman sitting on the man in the elevator. "My women aren't all that pretty, not like covergirls. But they're—okay. But not beautiful. Merely they're similar real women that way. I told Michelle that fashions modify. And today, women—in movies, on tv, in advertisements—look like ordinary women, not like movie stars. They await similar my women," he said with a grin.

There are doubtless still several Dedini cartoons in the Playboy inventory, awaiting publication. One showed up just the last year or then. The New Yorker also has quite a store of Dedini cartoons. One of the things that puzzled him at most the time nosotros talked was that the magazine connected to purchase cartoons from him but didn't publish them. One summertime, he vowed he'd spend the next month concentrating on New Yorker humor, adamant to break into print there over again. But The New Yorker still hasn't published a Dedini drawing since. A puzzle.

For the last month of his life, December 2005, Dedini stayed at habitation nether hospice care which kept him relatively pain-gratis and comfy. He had been contesting esophageal cancer for the final six months or so. His son Giulio came from his abode in San Luis Obispo and moved in to stay with him and his mother. Then did the cartoonist's younger brother, Delwin, fourscore, who however lived at the family ranch about Altadena. Friends dropped by, and he enjoyed them, Giulio told me. Even though he hadn't the stamina for long chat, Giulio said, "He makes us laugh every solar day."

And he continued to drawn in his sketch/scrapbook, formulating gags, listing conversational scraps that might be useful as captions for cartoons.

Dedini wanted his papers and original fine art to be archived at Ohio Land Academy's Cartoon Research Library. On Mon, January nine, Jenny Robb, so Visiting Assistant Curator of CRL (and now curator of the newly named Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum), arrived to arrange packing upwardly and shipping the materials. When she came in to meet Dedini, he was delighted to run into a pretty young woman, and, the eternal gentleman, he saturday up in bed right away to engage her in conversation.

The cartoonist was extraordinarily meticulous in maintaining the most comprehensive of files. The White Business firm notation requesting the Jackie Kennedy cartoon is filed with associated clippings and other correspondence about the final disposition by auction of the original. And then well organized was the material that it took only a day-and-a-half to pack it all up in nearly 100 boxes. By the end of the day on Midweek, Giulio told me, the boxes and 2,000 originals were on a truck spring for Ohio.

"I went in to tell him that it was all done," Giulio said, "—all his papers and his originals were safely on their manner—and he could rest easy at present. And certain plenty, the adjacent mean solar day, he did. That's when he died."

Reuben Pearson, a printer and poet and a PBL denizen, described Dedini equally "gentle and Italianesque, a wielder of castor and Rapidograph, who viewed life through a twinkle and who must ever be counted as one of Sky'southward creatures who are splendidly whole." His eye lost none of its twinkle: he kept on making people effectually him express mirth every day, funny to the last.

Here'due south a too curt gallery of copies of pages from Dedini's sketch/scrapbooks, glimpses of the inside of his playful and always congenial cartooning mind.

Source: https://www.tcj.com/viewing-life-through-a-twinkle/

0 Response to "Any Happier I Would Just Pop Playboy Is Naked Again Cartoon"

Postar um comentário